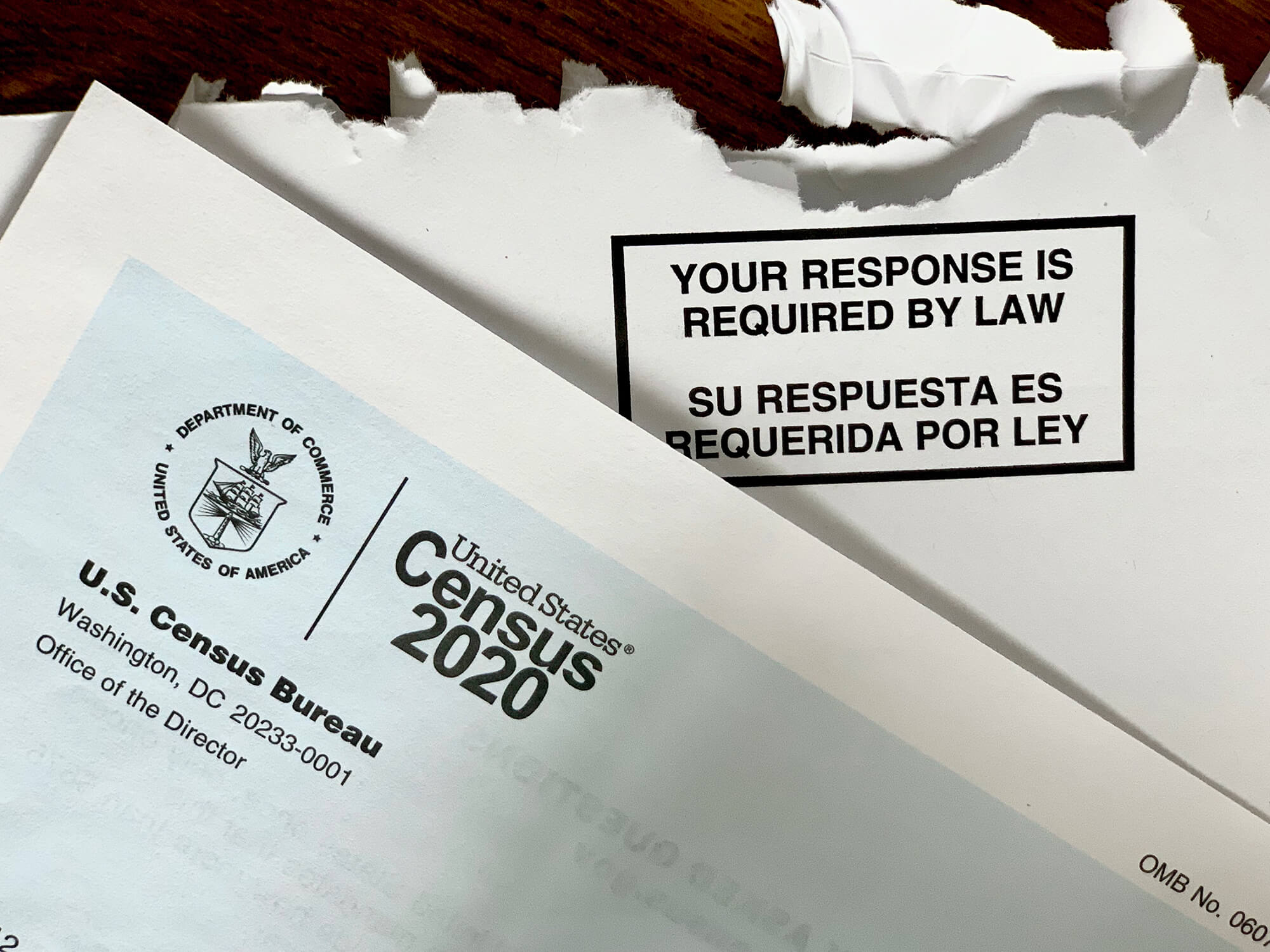

You know what is inefficient? The US census. In the modern age, why are we trying to print out a form for everyone in the United States to fill out, put it in an envelope, slap a stamp on it and then send it to every single address? And then, as a backup measure, send someone driving around door to door to make sure people fill out the form (often carrying another copy with them), only to have huge numbers of people still not participate? Why on earth would we spend so many resources in paper, people, time, gas, and money when this kind of thing could be done in other ways?

What’s more, the data quality is remarkably low. How low? So low that the Census Bureau felt it necessary to point out that there is “little” evidence of falsified data in the census. They say only about 0.4% of respondents likely falsified data. One wonders how that gets verified or what is meant by falsified data. The word “falsified” implies intent. Yet, how does that account for unintentional inaccuracies? Or people filling out their forms either just before or after they moved?

Regardless, the Census Bureau was concerned enough about data inaccuracy that they did follow up interviews with over 300,000 households. That’s a pretty big response requiring yet more resources, all in the hopes of achieving greater accuracy.

Why does accuracy in the census matter so much? The biggest reason is that it directly affects representation in the state and federal legislatures. The amount of seats in the House of Representatives is directly affected by population. Population numbers, demographics and other data are also important to the distribution of 1.5 trillion dollars in federal funds as well. Or to put it another way, how your tax dollars are distributed and who makes those decisions are directly affected by the accuracy of the census data. Needless to say, it’s important to find the best, most accurate methods of gathering that data possible.

So, what reasons do we have to assume that the data is inaccurate beyond mere accusations? We know that they will sometimes rely on data from landlords, friends and family members if some people don’t respond directly. Some census agents have even been directed to make guesses based on the number of cars and bikes out in the driveway, or even by looking through people’s windows. There are so many problems with that, it’s hard to even know where to begin. A family could be on vacation so no one is around for a while, or they could have friends over for dinner, meaning there are extra cars parked out front. And are we seriously okay with the idea of government employees lurking around our yards peeking into the kitchen windows. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to figure out all sorts of ways that could go wrong.

Sadly, this is often the case with data gathering overall. The census is just the archaic dinosaur version of data skimming, cookies, and selling your data to third parties without your consent. There are inaccuracies, falsifications, guesses and deceptions everywhere that some motive other than accurately representing people is present. Whether those other motives are profit or getting your manager off your back, it all leads to poor data quality.

What if the Census Bureau took a different approach? Rather than spending all sorts of money and effort to get people to take the time to fill out a form and send it back when there is no immediate reward for doing so they worked with TARTLE? They could offer a financial incentive to people to respond to all the same questions from their phone and get a financial reward in the process? It would be faster, more efficient, and almost certainly more accurate, especially if people could choose to send pre-existing data packets that already reflect exactly the kind of information the Census Bureau is after. By making use of the TARTLE data marketplace, the government would get a better understanding of the population and better represent it in Congress and in funding.

What’s your data worth?

You know what is inefficient? The US census. In the modern age, why are we trying to print out a form for everyone in the United States to fill out, put it in an envelope, slap a stamp on it and then send it to every single address? And then, as a backup measure, send someone driving around door to door to make sure people fill out the form (often carrying another copy with them), only to have huge numbers of people still not participate?

Automated (00:07):

Welcome to Tartle Cast, with your hosts, Alexander McCaig and Jason Rigby, where humanity steps into the future and source data defines the path.

Alexander McCaig (00:25):

Hey Jason, and listeners. In my mind, there is nothing more inefficient, than taking a huge piece of paper... First of all you have to log down a tree for this thing, press it into some sort of milling process, turn it into paper, ship it over to a printing company, have them print this thing out in some sort of variable print machine, stick it in an envelope, which is more paper, inked on top, and then ship that to all of these different addresses across the United States by hand, someone had to deliver it by hand.

Jason Rigby (00:56):

You know what's even more inconvenient than that? Is having a person knock on every single person's door in the United States.

Alexander McCaig (01:03):

You had to follow up with them.

Jason Rigby (01:04):

And to take that same piece of paper, and follow up with them. You know how much gas... We have the internet.

Alexander McCaig (01:12):

What a carbon footprint nightmare, doing the census here in the United States. And not only is it completely... It's just totally non-environmental, is that the data sucks.

Jason Rigby (01:28):

Yeah. Data quality. That's what we're going to talk about.

Alexander McCaig (01:29):

Data quality is low.

Jason Rigby (01:31):

MarketWatch.com says the Census Bureau finding little evidence of falsified data in 2020 population count. That title sounds great, but when we delve into it-

Alexander McCaig (01:43):

You got to think about the tone of the title. Read it one more time.

Jason Rigby (01:45):

Census Bureau finding little evidence of falsified data in 2020 population count.

Alexander McCaig (01:49):

Okay. So the Census Bureau finds little data. They themselves are looking at themselves and going, "We found little data on any sort of false information."

Jason Rigby (01:58):

Well, what they're worried about is the shortened schedule due to COVID jeopardized data quality. The US Census Bureau on Thursday said less than half a percent of census takers interviewing households for the 2020 head count may have falsified their work, suggesting such problems were few and far between.

Alexander McCaig (02:13):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (02:13):

So let me ask you something. Companies are decentralizing and they're adapting to COVID.

Alexander McCaig (02:19):

Yeah. Why-

Jason Rigby (02:20):

So why hasn't the system, that they've done for... How many years have they done this?

Alexander McCaig (02:27):

So long since this has been out.

Jason Rigby (02:28):

Why didn't they say, "Oh. Well, let's find a cheaper, more efficient, more environmental friendly way to do the census, that's safe and secure?"

Alexander McCaig (02:36):

And more accurate.

Jason Rigby (02:37):

Yes. Should we invest in this new thing called blockchain?

Alexander McCaig (02:40):

Yeah, we know. We probably should. Should we have bought our data pack on census from Tartle [crosstalk 00:02:44].

Jason Rigby (02:44):

Yes. And we could have asked them directly these questions.

Alexander McCaig (02:47):

I don't have to send someone to their house. I can just ping them with a notification message.

Jason Rigby (02:50):

And so all the money they pay for the postage, and the gas and these... What do you call the people that do it? Enumerators or whatever they call-

Alexander McCaig (02:58):

Enumerators.

Jason Rigby (02:59):

Yeah, enumerators. All this-

Alexander McCaig (03:01):

Enumerators. It's like a driver for data.

Jason Rigby (03:02):

We could have turned around and paid somebody to fill out the census. How much more would you have gotten if you had incentivized them through Tartle, to fill out the census.

Alexander McCaig (03:12):

Rather than having to have someone knock on your door, who you don't even know, and you're like "Get off my property."

Jason Rigby (03:16):

You know how... There's a religion that knocks on people's door.

Alexander McCaig (03:19):

Jehova's Witness.

Jason Rigby (03:19):

Yes, and Mormons.

Alexander McCaig (03:19):

And Mormons.

Jason Rigby (03:22):

And people hate that. I don't see them as much around anymore. I think people have gotten away from the knocking on the door and sending people to hell.

Alexander McCaig (03:29):

It's not a great approach. It's not the strongest approach to incentivize someone to do something you want.

Jason Rigby (03:34):

Yeah. And I would like to look at the data from the Mormon church during COVID, when they're not having people knock on doors, see if they still grew or not.

Alexander McCaig (03:43):

Ask them, "Did you lose subscribers?"

Jason Rigby (03:48):

Oh, my Lord.

Alexander McCaig (03:49):

No pun intended.

Jason Rigby (03:50):

Hey, I know everybody has different types of religions and stuff like that. And we love Mitt Romney. He was a Mormon. We love everyone.

Alexander McCaig (03:58):

Everyone-

Jason Rigby (03:59):

I don't want to be divisive.

Alexander McCaig (04:00):

Yeah. Everyone gets the same amount of love here.

Jason Rigby (04:02):

Yeah. So whatever type of... I know we're making fun of the Mormons, but at the end of the day-

Alexander McCaig (04:09):

We're not making fun of them, we're just making fun of the process.

Jason Rigby (04:10):

Yeah, exactly.

Alexander McCaig (04:11):

It's a bad process.

Jason Rigby (04:12):

Yeah. It's a bad process.

Alexander McCaig (04:13):

When is the last time of-

Jason Rigby (04:14):

Because I love Utah, amazing. Salt Lake City. The Portland Temple.

Alexander McCaig (04:21):

Think about it, dude. When is the last time a British imperialism worked out?

Jason Rigby (04:25):

Oh. Yeah, exactly.

Alexander McCaig (04:26):

When's the last time invading someone's country, and then forcing them to act in your way-

Jason Rigby (04:30):

Yeah, worked out.

Alexander McCaig (04:30):

Yeah. Can I knock on your door-

Jason Rigby (04:31):

We're still having issues.

Alexander McCaig (04:33):

Yeah. "Can you do our census?" "No, stranger."

Jason Rigby (04:35):

Yes, exactly. Yeah. So when we get into data quality, the agency sent a statement that a preliminary look at the data suggests 0.4% of the hundreds of thousands of census takers may have either falsified data, or performed their jobs unsuccessfully.

Alexander McCaig (04:52):

Are you incentivized to be like, "I'm going to put the time into this", or is it just a thing you do? Are you going to be like, "Oh yeah, fuck it"? I guess I fall into that category, "Whatever. I'll check this off. This is me. Oh, they have it marked to the wrong address, but I'll fill it out anyway, even though they moved."

Jason Rigby (05:11):

Yeah. But here's the problem, and I want people to understand just how important the census data is.

Alexander McCaig (05:14):

Please.

Jason Rigby (05:15):

The Census Bureau issued a statement after a report from its watchdog agency, Wednesday, that expressed concerns over lapses and quality control checks on the data use, for deciding how many congressional seats each state gets, and how 1.5 trillion in federal funding is distributed each year.

Alexander McCaig (05:34):

Because of the census.

Jason Rigby (05:35):

We get that because of the census.

Alexander McCaig (05:35):

Yeah. The census is deciding-

Jason Rigby (05:36):

You see what bad data does?

Alexander McCaig (05:37):

It wastes money. It wastes precious resources. And if you wanted that park built, and you lied on your census data because you weren't incentivized to do it properly, and the people analyzing it are saying it's legit, when it really isn't?

Jason Rigby (05:47):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (05:48):

Park's not going to be there.

Jason Rigby (05:49):

Think about that. The census is the filter. These people knocking on your door, it's the filter, not only for your congressional seats, but for 1.5 trillion tax freaking dollars.

Alexander McCaig (06:00):

Do you even know what a trillion looks like? You can count to it in a lifetime, because it's so big.

Jason Rigby (06:05):

This is how they distribute it.

Alexander McCaig (06:07):

This is how it's distributed. It's distributed in the most inefficient manner possible.

Jason Rigby (06:12):

So the office of Inspector General, the lapses raised concerns about the quality of the census data. And this was the report the office of Inspector General said. The report said the Census Bureau failed to complete 355,000 re-interviewed of households to verify their information was accurate. And we're going to get more into this.

Alexander McCaig (06:30):

That's because they didn't want to pay for the person to go out there and go ask them.

Jason Rigby (06:32):

Re-interviews were also not conducted with more than a third of the census takers, who completed a household interview. And 70,000 cases that were red flagged for re-interviews were given a pass, even though a census clerk was unable to determine if the original interview data was correct.

Alexander McCaig (06:45):

How do you know if it's correct?

Jason Rigby (06:48):

But think, about a third of the nation's 130 million households required visits from census takers, while residents and the remaining two thirds of households self responded, either online, by phone, or by mail.

Alexander McCaig (06:58):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (06:59):

Because of the failure to conduct the re-interviews, the Census Bureau can't provide a full picture of the falsification that may have taken place. So where did they come up with the 0.4%?

Alexander McCaig (07:08):

Yeah. How do you mean you can't come with a clear picture, but you can give me a percentage?

Jason Rigby (07:12):

That was Rob Santos, President of American Statistical Association. And he said this, and I love this, "Just like with COVID testing, you won't find it, if you don't look for it."

Alexander McCaig (07:19):

Yeah, that was a great point. And let me ask you something. Why does the US government wait to do this census after whatever body of time, and then decide they have to put the funds out? Why don't you just on a rolling basis, always do a census on people?

Jason Rigby (07:33):

Yes. Could you imagine how much it costs them to do 355,000 re-interviews? And to also have people go talk to 130 million people.

Alexander McCaig (07:43):

How much time does it take?

Jason Rigby (07:44):

How big of a system is that?

Alexander McCaig (07:45):

The government can do it in 24 hours with Tartle. 24 hours, re-interview whoever you want.

Jason Rigby (07:50):

Yeah. And then let's compare that data with your data, and see how it goes.

Alexander McCaig (07:53):

Oh. And by the way, you buy it? We're going to buy it too.

Jason Rigby (07:56):

But this is a bigger picture, a big macro picture, that I want us to talk about, that's going to help a lot of companies that are listening to this. And I think it just proves Tartle over and over again. The article talks about this. There are other concerns about data quality, besides falsification, such as inconsistent responses, and the reliance on getting information from neighbors or landlords for residents of households weren't available. And then Santos, same guy, at American Statistical Association said this, "Where are the assessments of these aspects of quality?" So not only we have issues of falsification-

Alexander McCaig (08:29):

But it's actually how the data is retrieved.

Jason Rigby (08:31):

We have inconsistent responses, and then the reliance on getting that information.

Alexander McCaig (08:34):

So we have the quality [inaudible 00:08:36] retrieval, how many holes are actually in the data, and then trying to fill those holes with what you think is the right answer, and then giving it out to the public, that does not seem like three strong legs of a stool I would want to sit on.

Jason Rigby (08:52):

Would you?

Alexander McCaig (08:53):

Yeah. Would you?

Jason Rigby (08:54):

Would you? If you were CEO of the US Census, could you honestly say that that data is accurate?

Automated (08:59):

Yeah. Our camera on this tripod would fall over. A tripod.

Jason Rigby (09:04):

Tripod.

Alexander McCaig (09:05):

We all can just rotate, and [crosstalk 00:09:06] .

Jason Rigby (09:06):

That would be awesome. Yeah.

Alexander McCaig (09:07):

Yeah, like why would you... The government's like, "Okay. We've got a bunch of bad data, how do we give the money out?"

Jason Rigby (09:12):

And shout to this Rob Santos, he says this too, "There are arguably more important than falsification, because they will be more prevalent."

Alexander McCaig (09:20):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (09:20):

So when you think about data, and-

Alexander McCaig (09:22):

I don't really care about people falsifying. I just want to make sure that everything else is totally quality.

Jason Rigby (09:26):

Because we know data, in and of itself, doesn't have an opinion.

Alexander McCaig (09:29):

No.

Jason Rigby (09:30):

So it's now, we're basing it off of inconsistent responses, and the reliance on getting the information. So we're relying on a human to get that information. And yeah, we've incentivized them, but we've also... How we've incentivized them is to say, "Well, what if I just fill this form out real quick. Okay. I got that one done, and then I've met my quota."

Alexander McCaig (09:50):

Oh. Why don't you show them each question, and what impact each of those questions has? How is this specific question going to be analyzed?

Jason Rigby (09:57):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (09:58):

Then the person's like, "Oh, interesting. So this is going to accrue to parks being built in my area. Oh, cool."

Jason Rigby (10:03):

But whenever I look at data quality, and I see people amassing this large amounts of data, and the way they get the information, and in this inconsistent responses that they're getting, and then this way that they're getting it nefariously by spying on people with cookies and all that stuff, it's the same situation. The US Census Bureau to me, yeah, it's a big governmental agency, but it's the same thing that we're looking at when we look at quality of data throughout the world.

Alexander McCaig (10:34):

Throughout the world. Yeah. And all these other companies that are housing this data.

Jason Rigby (10:38):

Because we're just doing hunches, bro. We would talk about this over and over again.

Alexander McCaig (10:42):

It's hunches all day long. You know what's great? Like hospitals, they got all this financial bleed, but they say, "Hey, we're doing really well. Look, we have our own metrics." "I'm sure you do, but you're still just gripping to have people come through the front door, aren't you? You really want to bill on that emergency room code."

Jason Rigby (10:57):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (10:58):

"But your net promoter score is 4.78." Big deal.

Jason Rigby (11:02):

Yeah. Where did those KPIs come from?

Alexander McCaig (11:04):

They make them up.

Jason Rigby (11:05):

Where did that come from?

Alexander McCaig (11:06):

They make them up.

Jason Rigby (11:06):

Yes. So the Associated Press says this... Has documented cases of census takers, being pressured to enter false information into a computer system about homes they had not visited, so they could close cases during the waning days of the once a decade national head count. Other census takers told the AP that they were instructed to make up answers about households, where they were unable to get information. In one instance, by looking in the windows of homes, and another by basing a guess on the numbers of cars in the driveway, or bicycles in the yard.

Alexander McCaig (11:38):

What if I got a party, I'm just saying. I think I'd have 25 cars in the driveway.

Jason Rigby (11:43):

That's what I'm saying.

Alexander McCaig (11:43):

But I'm in a depressed socioeconomic area, and people are like, "This guy must be loaded."

Jason Rigby (11:48):

But dude, doesn't this show? Think about it, Alex. Doesn't this show, what we've been harping on for the past few years, about the data having quality?

Alexander McCaig (12:01):

All the time.

Jason Rigby (12:02):

This is what we talk about.

Alexander McCaig (12:03):

You have to go to the source. You have to incentivize people at the source, to capture quality, truthful information, and don't wait 10 years to do it.

Jason Rigby (12:12):

Just because you drive a Prius, we talked about this before, because you drive a Prius and you go to Cabela's, how is the data's supposed to handle that, unless you ask?

Alexander McCaig (12:19):

The algorithm is crippling. It's like, "Ah. They've fallen to some-"

Jason Rigby (12:24):

You're supposed to go to REI, not Cabela's.

Alexander McCaig (12:26):

Yeah. "Should we send them a Democratic ad, or Republican based? Ah, I don't know what they're doing."

Jason Rigby (12:33):

And that's the problem we face. And so what begins to happen, when you have these questions, to make a profit, we begin to falsify.

Alexander McCaig (12:41):

We begin to falsify, and we begin to divide people where they shouldn't be.

Jason Rigby (12:44):

And then we begin to make hunches and guesses, and then we pressure data scientists, I know data scientists will agree with this 100%-

Alexander McCaig (12:49):

To come up with some sort of business intelligence, on what this might be, and there's tons of holes in the entire dataset.

Jason Rigby (12:57):

Data scientists, this drug needs to pass.

Alexander McCaig (12:59):

Yeah. So whatever you got to do-

Jason Rigby (13:01):

We have $80 billion riding on this.

Alexander McCaig (13:03):

Yeah. I want you to say it's 98% effective. And I don't care how you manipulate it with pivot tables, just put it in there like that.

Jason Rigby (13:10):

And they're not going to say it that way exactly to them, because they know that they would spend an eternity in.

Alexander McCaig (13:14):

And you know what's cool about Tartle? Can we just talk about that?

Jason Rigby (13:16):

And those Soft Plus gels.

Alexander McCaig (13:17):

Yeah, and the Soft Plus Gels. Multiple companies come in, and they can buy the same datasets. Then they'd be like, "No. Let's look at your analysis. Something about that's a little fishy here, because six other companies came together and we all bought this, and we all came to this conclusion, but something's off. Something's totally off. And here's the raw data."

Jason Rigby (13:44):

That's why Tartle's marketplace is so needed, especially if you're wanting to purchase data from us, because you can sit there and have it go against the data that you've already have, and analyze it and say, "Well, we know Tartle's marketplace, we've gone through it extensively. We understand how pure that data is." So let's see, if it aligns with your data, great.

Alexander McCaig (14:03):

Good for you.

Jason Rigby (14:04):

You did a great job.

Alexander McCaig (14:05):

You're on the right path.

Jason Rigby (14:05):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (14:06):

If it doesn't, there's some things we got to look at here.

Jason Rigby (14:09):

Now I can reverse engineer it and say, "I have a process that I can use, because I have a standard, and so I have a process that I can reverse engineer it, go through it and decide it, and be able to make a decision, not a hunch."

Alexander McCaig (14:22):

Not a hunch.

Jason Rigby (14:22):

And guess what's going to happen, when you have pure data, since data is the gold of the world. When you have pure data, that decision that you make is going to be accurate and keyword, everybody listen, dollar signs, profitable.

Alexander McCaig (14:34):

Profitable. Beneficial to you, and your customers. Isn't that incredible? Well, that seems so immensely logical. It gives me a nosebleed.

Jason Rigby (14:44):

Yeah. And it's simple.

Alexander McCaig (14:46):

It is so simple.

Jason Rigby (14:49):

The Census Bureau announced it will miss Thursday's deadlines for turning in the numbers, used for divvying up congressional seats, but aims to deliver. How many times have you heard that in shareholder? "We aim to deliver."

Alexander McCaig (15:01):

Hold on. Let me get my bow out. Hold on. I just got out of my Prius. I got my bow. I'm aiming to deliver, here.

Jason Rigby (15:11):

That's a key analogy, I love that. So now I'm dependent on the accuracy of the bow. I'm depending on the person that's shooting the bow. I'm depending on the arrows.

Alexander McCaig (15:19):

Yes.

Jason Rigby (15:19):

If you have a bent arrow, it doesn't matter how accurate you are. If your bow string's all messed up, it doesn't matter. And if you don't have any... If no one's ever shot that bow, they can't even pull the bow back hardly. So this aiming thing-

Alexander McCaig (15:31):

This aiming thing is ridiculous.

Jason Rigby (15:34):

It leads to too many variables. And as a leader of a corporation, why would I want to have that many variables out?

Alexander McCaig (15:40):

Let me ask you something. I'm holding the mic manually. Why am I waiting to do something? If I can get the information right now, why am I waiting to deliver it? Do I need to come up with some sort of idea in my mind? It is what it is. You don't need to change it into something it is not, or come up with some sort of story saying, "Oh. This is how we define it. This is our perspective, or do you mean to go this way?" No.

Jason Rigby (16:06):

Hold your mic again. This is what companies are doing with data. They're just holding it.

Alexander McCaig (16:11):

They're just holding it. Hold on. And then they're not talking, but they're talking like this, they're whispering. Let's talk around the thing that we need to do, rather than be like... Let's be very clear and direct and truthful with what needs to be said.

Jason Rigby (16:27):

And let's use all that data you've been collecting for how many years, to make a truthful decision that will help your company serve humanity.

Alexander McCaig (16:35):

Yeah. Elevate those data sets by actually... Take your census data and compare it to the Tartle data.

Jason Rigby (16:40):

Yes, exactly. And we'd love to have a conversation with the Census Bureau.

Alexander McCaig (16:43):

Yeah. Bring it on, let's go.

Jason Rigby (16:45):

So now we're going to divvy up congressional seats, and they said, "But aims to deliver a population count of each state in early 2021, as close to the missed deadline as possible." And then this is what the Census Bureau Director, Steven Dillingham said in 2020.

Alexander McCaig (16:59):

Well, Dillingham.

Jason Rigby (17:00):

"A year when the agency was conducting the census, amid a pandemic, wildfires, and hurricanes, has tested our patience, faith and strength. But despite all the extra noisy circumstances happening around the world, we have succeeded, through the tenacity and creativity of the women and men who work at this extraordinary agency."

Alexander McCaig (17:20):

Yeah. I bet you have.

Jason Rigby (17:21):

What is this? Winston Churchill.

Alexander McCaig (17:23):

What is so extraordinary about you collecting data in the most archaic format possible?

Jason Rigby (17:28):

Yeah. When you could have-

Alexander McCaig (17:29):

And failing to do so accurately. What is extraordinary about that?

Jason Rigby (17:32):

Yeah. And those people that helped you, and did that, and worked through that, and had to wear mask, and be uncomfortable, I get all that. But why did you put them through all that process? When you have something that is obscure, super easy.

Alexander McCaig (17:45):

I'm like melting in my chair, because-

Jason Rigby (17:46):

It's the same thing. I had to cut the TV off, when I'm watching people in 2021, well this was last year, 2020, well they're still doing it now in Georgia and elsewhere, counting ballots by hand.

Alexander McCaig (17:58):

Yeah. Come on.

Jason Rigby (18:00):

What is this?

Alexander McCaig (18:01):

You're telling me a human is going to be more consistent than a computer algorithm, first in, first out, like that's what it is, reads it very black and white?" What if the person is like, "Oh. I stuck two pieces of paper together in my fingers, because they weren't separating."

Jason Rigby (18:13):

And this gets me too, because I've heard a lot of people say this, "Well, I don't trust the computers." Yes you do. You trust them every single day.

Alexander McCaig (18:17):

You trust them every single day.

Jason Rigby (18:19):

Every time you get into your car-

Alexander McCaig (18:21):

And you turn it on, that's a computer system.

Jason Rigby (18:22):

You're trusting a computer.

Alexander McCaig (18:22):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (18:23):

Every time you get into that airplane-

Alexander McCaig (18:25):

Yeah. You're trusting a computer system.

Jason Rigby (18:27):

[crosstalk 00:18:27] Look how many crashes we've had.

Alexander McCaig (18:30):

Every time you go to a hospital, computer system. Go to work, computer system.

Jason Rigby (18:34):

You're trusting thousands of computers, every single day in every part of your life. And every single one of those are creating data. And what are you going to do with it?

Alexander McCaig (18:43):

But you don't trust them to count a ballot?

Jason Rigby (18:45):

Because you, Mr. CEO, are self-responsible for that data. You're collecting it, now... Stop collecting it, if you don't want the responsibility.

Alexander McCaig (18:54):

Yeah. You need to hold responsibility for that information.

Jason Rigby (18:58):

You are holding responsibility of millions of people, that whether you've tricked and got the data, or however you got the data, but you have that responsibility for that data, and that data will help humanity. And that therefore is your responsibility.

Alexander McCaig (19:11):

You have the responsibility to share what you've learned from it.

Jason Rigby (19:13):

And it is the responsibility of the Census Bureau. It is the responsibility of every private and public corporation that's out there, to understand how important data is.

Alexander McCaig (19:24):

Yeah. To really see the value in sharing truthful information.

Jason Rigby (19:28):

And what that can do.

Alexander McCaig (19:30):

Everybody does not need to act like the CIA. They don't have to act like the NSA. The NSA only benefits themselves, the NSA and the CIA. They keep the information to themselves. They don't want other governments to share in that information. They think it gives them some sort of upper hand, but really what it does is it polarizes the world. Yes, there are some aspects of people in the CIA and NSA that are beneficial that keep us safe, the things we probably never even realized were a threat, fantastic. But for the larger majority, the 99% of us, and all of our businesses, corporations, gloves, enterprises, farms, farmers, whatever it might be, sharing that information, we're going to solve all of our problems that the NSA really doesn't have to worry about all that crap.

Jason Rigby (20:06):

It doesn't have to. Stop collecting data and start using data.

Alexander McCaig (20:10):

Start using it. Start using it truthfully.

Jason Rigby (20:12):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (20:13):

And when you've come to a realization, when you become wise about it, share your wisdom.

Jason Rigby (20:18):

100%.

Alexander McCaig (20:19):

Thank you.

Automated (20:19):

Thank you for listening to Tartle Cast with your hosts, Alexander McCain and Jason Rigby, where humanity steps into the future, and source data defines the path. What's your data worth?