Net Zero? The old ISP? Nope, this would be referencing climate goals. Specifically to reach the goal of net zero climate emissions. Sounds good doesn’t it? And it is, but you may have noticed that the goal isn’t ‘zero’. It’s ‘net zero’. What that means is that reaching net zero emissions means that a company or country that sets that goal is doing something to offset their emissions. That could be a lot of things. It could be planting trees, contributing to renewable energy, or technology that reduces vehicle emissions. Depending on who is doing the counting, things like cleaning up landfills and recycling might be considered as offsetting some emissions. More on that sort of thing in a minute.

Many companies have announced their intention to reach this goal at some point in the future. The latest among these is credit giant Mastercard. However, you might want to hold the fireworks and the kazoos. Keep that champagne corked y’all. Why? Because the powers that be have set their net zero goal for 2050, a timeframe that was actually called ‘audacious’. Really? Thirty years is ‘audacious’? Next week, that would be audacious. And unachievable but that’s beside the point.

So why aren’t we celebrating? Isn't it good that Mastercard is at least trying? That’s the wrong question. The right question is, are they really trying at all with a goal like that? If the goal were five or even ten years, that might be considered trying. Thirty is a virtue signal. It’s made to make people think that they are trying.

I get it. That seems unfair. Stop to think though. How many times have you heard of some long term goal getting set by any organization and then heard of it actually being met? Whether we are talking about countries, the UN, companies, or charities, long term goals or pledges like that rarely amount to much. Just think of all the ‘moonshots’ the US government has announced over the years. Whether it’s going to Mars, curing cancer, eradicating poverty, etc. They never go anywhere.

The fact is, there isn’t any sort of long term planning ability in most organizations. Most executives won’t last anything like the amount of time needed to make the goal a reality. And that’s if they even mean it in the first place. So even if the current Mastercard CEO and Board of Directors are well intentioned, the chances of the next two or three having the same vision are pretty darn slim. And even if they were going to try to get somewhere with it, there are creative ways of accounting that could very easily be applied to the net zero concept. In fact, so many unrelated issues have been bound up with climate change and environmentalism in general in recent years that almost any donation to anything could wind up counting.

Let’s say for a moment though that Mastercard was actually interested in reducing its emissions and doing so in a reasonable period of time, how might it go about that? Well, the company has 180 data centers worldwide. They no doubt suck up a fair amount of electricity so that would be a good place to start. Is there a more efficient way to store and process the data? Could they actually collect less of it? Could the buildings those data centers are in be made more efficient so they take less to heat and cool? What if they powered the climate control systems at least from solar panels on the buildings in climates where that makes sense?

Mastercard could also do the classic thing and plant some trees. Surely they could spare money to take some brownfields and turn them into greenfields, something that would benefit the local community as well as the environment. There are plenty of options available to organizations that are willing to take the goal of net zero emissions seriously.

What’s your data worth? Sign up and join the TARTLE Marketplace with this link here.

Climate scientists spend a lot of time studying the past to predict the future. Now, you might be recalling all the times we’ve talked about the danger of thinking you can figure out the future just by studying the past. That certainly stands, but the fact is, you have to start somewhere. Going back to what has come before can provide a valuable baseline for understanding how one thing affects another and can contribute to the development of the climate over time.

One of the places scientists go to help understand the climate of past ages is the ocean, specifically the ocean bottom. They collect samples and study them for levels of a variety of different elements including calcium, strontium, magnesium, lithium, barium, and several more. These can give a snapshot of the past, giving scientists an idea of how much carbon is present in the ocean, the rate at which the crust is breaking down and more. However, these results might have been skewed because they left out contributions of groundwater.

Some scientists have brought up the idea that groundwater might be contributing these elements to the ocean but those concerns have typically been dismissed as insignificant. That, however, has changed with a new study by Kimberley Mayfield. The University of California doctoral candidate did her thesis on the subject. She built a library of hundreds of groundwater samples by begging them off of anyone she could. While still preliminary, that study shows that a surprising amount of the above elements are getting into the ocean from the groundwater when it leaches out into the rivers.

This is also important for the climate in other ways as these elements also contribute to the growth of phytoplankton near the mouths of rivers. Phytoplankton are tiny little critters that form the basis of significant parts of the food chain. When there are more of them, it can help fuel populations of other species of marine life. However, if other factors are depressing the fish population, the plankton can grow out of control and wind up using other resources and wind up choking out other life.

No doubt Mayfield’s study will help drive other work that will improve our understanding of the ocean and its effect on the climate. It’s also a good illustration of the TARTLE model at work. No, she didn’t use TARTLE but what she did is use a system that isn’t very different. In getting groundwater samples from many different people in many different walks of life, she unknowingly adopted a very TARTLE-like process. She solicited data straight from the source and used it to draw her conclusions.

Future researchers can do the same through TARTLE’s digital marketplace. What’s more, it would be possible to conduct research into what is going into the groundwater. By asking users to share data on how much bleach, detergent, and other household items they use, scientists could get a solid picture of how much of all of that is getting into the groundwater. That information could then be combined with data from groundwater samples. If the process is repeated for several regions it would be possible to see clearly how much environmental impact one person has based on his daily habits. We would actually be able to develop a more accurate climate model using information that covers every stage from the manufacturing of various products, to those products being used, to the groundwater and out into the ocean. This kind of analysis has become possible only recently but it will be sure to be invaluable in the near future. That’s the kind of thing TARTLE makes possible, we open up the opportunity for average people to contribute to the greater understanding of the world we live in and how we affect it.

What’s your data worth? Sign up and join the TARTLE Marketplace with this link here.

It looks like 2020 was Europe’s warmest year on record, going up 0.72F over the previous year. Well, that’s Europe, right? Sure. Worldwide, 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest year. Which puts us at 2.2F warmer on average than the planet was back in the pre-industrial period according to the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. Now, I don’t care who you are, but that’s something that should get your attention.

How much should it get your attention? Well, sustained warmer temperatures mean more melting ice which could cause some problems for coastal areas in the near future. How long will that take? Perhaps the best answer to that question is, ‘why does that matter?’ Instead of asking whether we need to put up sandbags or the grandkids will, maybe the better question is, ‘what can we do about it?’

What indeed. After all, we’re just individuals who are trying to muddle through life as best as we can. We don’t set policy, most of us don’t control massive corporations that can make the necessary advances to minimize or even roll back pollution. However, we are still people who can influence all of that. How? By sharing our data. Sharing our behaviors, how much we produce and consume and exactly what it is that we produce and consume. That information can help organizations to see what policies are effective in incentivizing various behaviors and which are failing. It can also help guide companies concerned about the environment to see where there is a demand for different products that will help contribute to reducing carbon emissions.

A prime example is in transportation. Electric cars have been getting a lot of press lately, and not without reason. The advances in that realm have been significant. However, the process to produce the necessary batteries are not necessarily environmentally friendly. That process leads to a lot of heavy metal pollution, to say nothing of the fossil fuels needed to produce them. And of course, most of the power used to charge those batteries comes from either fossil fuel plants or inefficient wind farms. So, how can our data help drive alternatives?

If general dissatisfaction with the current situation is known, companies are more likely to research alternatives like hydrogen power. Already, it’s possible to add hydrogen power to a conventional vehicle as a supplement. Turning it into something that could power the whole vehicle is just a matter of scale.

Of course, city planners can also make use of data from the locals to change zoning laws, allowing for more small shops to exist in what are currently residential areas. Or more homes in shopping districts in the form of apartments above businesses or restored brownfield projects. These approaches incentivize people to drive less not through coercive penalties and burdensome taxes but by simply making it easier to walk to where you want to go. Instead of having to drive ten to twenty minutes to go to a grocery store or a coffee shop, a person could just walk out the front door for a ten-minute stroll.

Yes, those seem like small things that at best can make local life more pleasant. Yet, just like humanity is made of individuals, so the planet is made of particular places. If the environment improves in a number of those particular places, it will necessarily improve things for the planet as well.

So, what can you do? Sign up with TARTLE and make your data available to the policymakers and companies that are trying to improve the environment for you and your kids. Then, instead of taking the earnings, you can donate them back to the organization of your choice so they can get more quality data to make better decisions and recommendations. That’s how it works, one small action at a time.

What’s your data worth? Sign up and join the TARTLE Marketplace with this link here.

Vivaldi’s Four Seasons is one of the greatest and most well-known pieces of classical music around. Nearly everyone (and I mean everyone) has heard at least some part of it whether they know it or not. The great composer wonderfully captures the feel of each season through sound. Spring is light and joyful, while winter is starker, more foreboding. It’s simply a masterpiece that orchestras around the world play on a regular basis. Now, several orchestras have taken on the task of interpreting Vivaldi’s great work in what can best be described as a novel approach.

The approach was developed with the help of AKQA, a communications and design group working in conjunction with data scientists to reflect predicted changes to the climate in the next fifty or so years. However, rather than making one composition that would be played everywhere, they used the algorithms they specially developed for the purpose to create hundreds of new versions, each designed to evoke the climate changes in various locations around the globe. The one for Shanghai is actually completely silent. That’s because the computer models they were using show that city being underwater by then. No, I’m not sure how many tickets they plan on selling. Some sort of original introit describing the fall of the city might be more interesting, but they didn’t ask me.

I digress. The point of the exercise is to alert people to the kinds of changes that might be coming their way, even within their own lifetimes. The team that developed these new renditions of The Four Seasons will be working with orchestras around the world to perform their work, with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra having signed to perform the first public rendition. Where it goes from there is less important than any effect it might have on those who listen to it. Will it actually encourage the listeners to care about and take some sort of action on the environment? And if so, how?

Very often, the way people take action on the environment is to vote for a politician or maybe take up a particular cause. Well, no policy is going to fix everything, no amount of money thrown at the problem is going to just make it go away. What will change things is changing your own behaviors.

Want fewer carbon emissions? Keep your house a couple degrees cooler in the winter and ride your bike to the corner gas station ten minutes away instead of driving twenty to get to the grocery store for that gallon of milk. Or install geothermal heating. Worried about straws? Instead of switching to a paper one, don’t use one at all. After all, someone had to cut down a tree for the paper straw.

Speaking of straws, if you are a restaurant, at least try to be consistent. Right when the straws were a big deal in the news I went to a restaurant that had signs proclaiming their commitment to not using plastic straws. And then they brought my drink in a plastic cup and when I got my food, I ate it with plastic cutlery. You can’t make this stuff up.

What else? Encourage people to take care of the things that are right in front of them. It’s a lot easier to point out the landfill down the road, or the river you want to keep clean and get people to care about keeping that in good condition than it is to get them to take drastic action based on a computer model. It’s too abstract for most.

In a way, that’s what the people behind this new interpretation of Vivaldi are trying to do, to make the abstract tangible. However, if you really want to change things, start with your own behaviors and help others to make better decisions on their own. With enough people changing their behaviors in that way, it will have a much bigger effect on global climate, while improving things in your local area, too.

Naturally, one thing you can do is to share your behaviors through TARTLE. That way, businesses and researchers can determine what kind of policies are working, or might work, what products people are buying to minimize their environmental impact and what particular issues most people care about. Your data can help with all of this and more.

What’s your data worth? Sign up and join the TARTLE Marketplace with this link here.

Few topics in the modern day are more contentious than that of climate change. Well, let’s face it, almost every topic is contentious today but climate stability has been the subject of much debate for decades and that doesn’t look to be changing anytime soon.

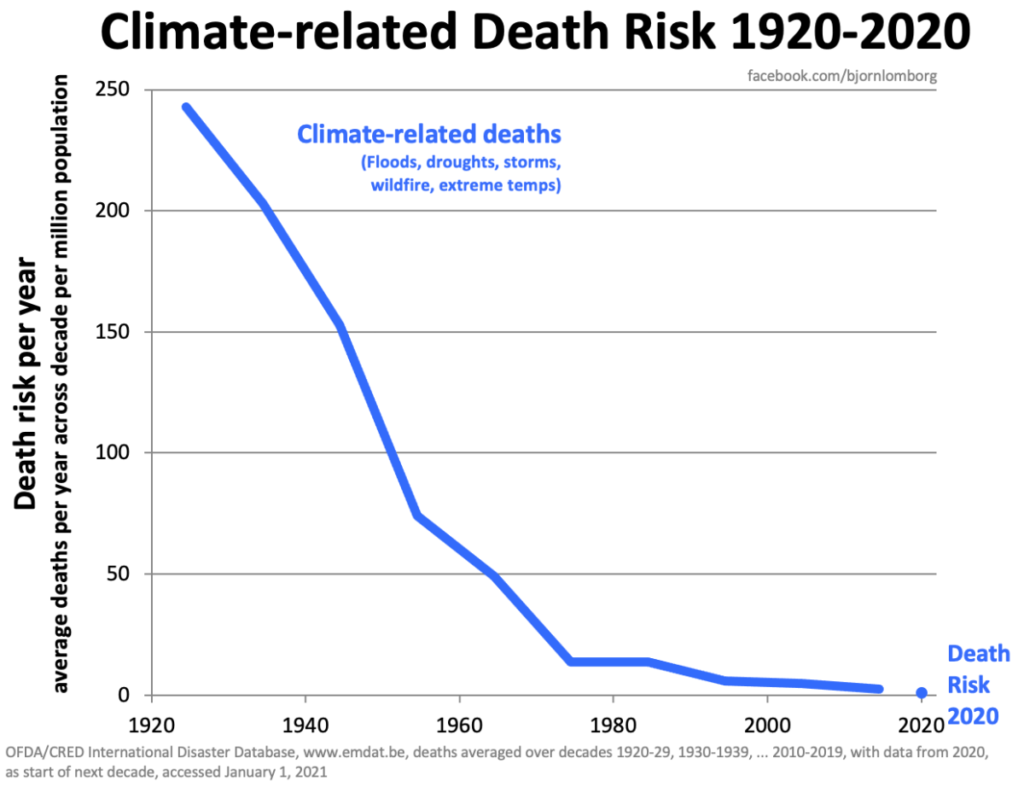

This fact has just recently been demonstrated yet again by a recent study released by Bjorn Lomborg that looks at the effects of climate change. One part in particular is interesting, which would be the graph.

The graph in question shows the number of deaths related to climate plotted out from 1920 to 2020. Climate-related deaths here means anything involving flood, droughts, wildfires, extreme hot or cold temperatures, and storms.

This graph has garnered a great deal of attention because it shows the deaths going from around 250 per million per year in 1920 to virtually none today. Many people are looking at this graph and deciding that climate change isn’t anything to be concerned about.

On the face of it, this isn’t a totally unreasonable conclusion. However, there are a couple of important points to emphasize. The first and most significant is that no one should be reaching conclusions about anything based on one graph, or on any other single point of data for that matter. The second point is related, one graph, while reflecting something true doesn’t necessarily take any number of other data points into consideration.

What do we mean? First, for the sake of argument, we’ll take the numbers presented for granted, that the numbers of climate-related deaths for each year are what the graph says they are. After all, the article is only a few pages and there isn’t time or space here to dig deep into the methodology. Second, we should stop and consider some reasons that climate-related deaths might have gone down other than climate change not being a thing. After all, even if we don’t take other factors into consideration, the graph doesn’t really argue against the idea of climate change. Rather, it would seem to argue that climate has gotten better, which virtually no one believes.

What are some of these other factors we should consider? These are mostly centered on the fact we have made a lot of material advances in the last hundred years. Our medical treatments have improved by leaps and bounds since 1920, dramatically improving life expectancies. We live longer and healthier so what once might have been major changes in air quality or temperature swings can be managed by individuals much better than before.

Housing for vast numbers of people has improved as well. While once, a major thunderstorm could have destroyed rudimentary shacks out on the prairie killing everyone inside, now there are sturdy homes with concrete basements that can handle anything short of a tornado.

Disaster response has also gotten much better. While today, helicopters deliver pallets of sandbags to flood zones practically on demand or patrol areas looking for people to rescue, or airplanes dump tons of water scooped out of a local lake onto a wildfire, such technology didn’t even exist outside of a notebook in 1920.

Related to that is the fact there have been major migrations to the cities which by their nature are less susceptible to climate-related issues. A big contributor is the rise in quality and affordable heating and cooling. In 1920, the relief from a blistering hot summer was a breeze or a cool stream, not turning up the AC. It’s the same with heating. How many people froze to death in 1920 while it is practically unheard of today?

None of these things seem to be considered in this graph of death rates, yet factors like this are necessary to get the whole picture. That’s why TARTLE is such a proponent of getting accurate data from as many direct sources as possible. When you are dealing with large samples of high quality source data, you get a better and less skewed view of the whole picture.

What’s your data worth? Sign up and join the TARTLE Marketplace with this link here.