Few topics in the modern day are more contentious than that of climate change. Well, let’s face it, almost every topic is contentious today but climate stability has been the subject of much debate for decades and that doesn’t look to be changing anytime soon.

This fact has just recently been demonstrated yet again by a recent study released by Bjorn Lomborg that looks at the effects of climate change. One part in particular is interesting, which would be the graph.

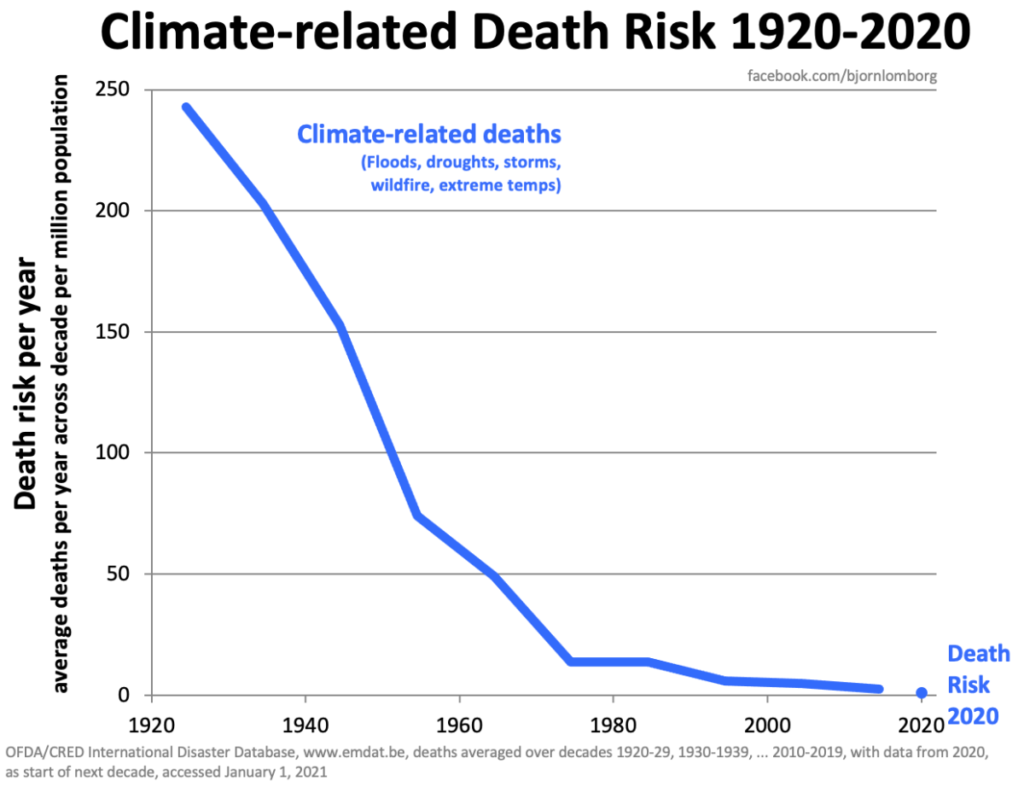

The graph in question shows the number of deaths related to climate plotted out from 1920 to 2020. Climate-related deaths here means anything involving flood, droughts, wildfires, extreme hot or cold temperatures, and storms.

This graph has garnered a great deal of attention because it shows the deaths going from around 250 per million per year in 1920 to virtually none today. Many people are looking at this graph and deciding that climate change isn’t anything to be concerned about.

On the face of it, this isn’t a totally unreasonable conclusion. However, there are a couple of important points to emphasize. The first and most significant is that no one should be reaching conclusions about anything based on one graph, or on any other single point of data for that matter. The second point is related, one graph, while reflecting something true doesn’t necessarily take any number of other data points into consideration.

What do we mean? First, for the sake of argument, we’ll take the numbers presented for granted, that the numbers of climate-related deaths for each year are what the graph says they are. After all, the article is only a few pages and there isn’t time or space here to dig deep into the methodology. Second, we should stop and consider some reasons that climate-related deaths might have gone down other than climate change not being a thing. After all, even if we don’t take other factors into consideration, the graph doesn’t really argue against the idea of climate change. Rather, it would seem to argue that climate has gotten better, which virtually no one believes.

What are some of these other factors we should consider? These are mostly centered on the fact we have made a lot of material advances in the last hundred years. Our medical treatments have improved by leaps and bounds since 1920, dramatically improving life expectancies. We live longer and healthier so what once might have been major changes in air quality or temperature swings can be managed by individuals much better than before.

Housing for vast numbers of people has improved as well. While once, a major thunderstorm could have destroyed rudimentary shacks out on the prairie killing everyone inside, now there are sturdy homes with concrete basements that can handle anything short of a tornado.

Disaster response has also gotten much better. While today, helicopters deliver pallets of sandbags to flood zones practically on demand or patrol areas looking for people to rescue, or airplanes dump tons of water scooped out of a local lake onto a wildfire, such technology didn’t even exist outside of a notebook in 1920.

Related to that is the fact there have been major migrations to the cities which by their nature are less susceptible to climate-related issues. A big contributor is the rise in quality and affordable heating and cooling. In 1920, the relief from a blistering hot summer was a breeze or a cool stream, not turning up the AC. It’s the same with heating. How many people froze to death in 1920 while it is practically unheard of today?

None of these things seem to be considered in this graph of death rates, yet factors like this are necessary to get the whole picture. That’s why TARTLE is such a proponent of getting accurate data from as many direct sources as possible. When you are dealing with large samples of high quality source data, you get a better and less skewed view of the whole picture.

What’s your data worth? Sign up and join the TARTLE Marketplace with this link here.

Few topics in the modern day are more contentious than that of climate change. Well, let’s face it, almost every topic is contentious today but climate stability has been the subject of much debate for decades and that doesn’t look to be changing anytime soon.

Speaker 1 (00:07):

Welcome to TARTLEcast with your host Alexander McCaig and Jason Rigby. Where humanity steps into the future and source data defines the path.

Jason Rigby (00:21):

Alex?

Alexander McCaig (00:22):

Yeah

Jason Rigby (00:23):

I was thinking, I think we need a TARTLE turtle,

Alexander McCaig (00:27):

Oh like a pet turtle?

Jason Rigby (00:28):

No, no. The big ones that live forever.

Alexander McCaig (00:30):

Oh, a tortoise.

Jason Rigby (00:31):

A tortoise. Yeah. At the headquarters, TARTLE headquarters. We'll have the TARTLE turtle.

Alexander McCaig (00:36):

Fun little fun side note story, so I'm on the Jersey shore. Oh, [crosstalk 00:00:43] don't put me in a, in the show.

Jason Rigby (00:44):

You're not on the show.

Alexander McCaig (00:45):

No, no I'm literally on the Jersey shore. Nobody put me in a bucket here and I'm on the inter-continent.

Jason Rigby (00:50):

Don't put baby in a corner.

Alexander McCaig (00:51):

Yeah don't put a baby in a corner film. I'm on that Intercontinental passageway for boats.

Jason Rigby (00:58):

Right.

Alexander McCaig (00:59):

Where you don't have to go out to the sea, but you can just you know, follow this thing essentially down to Florida. It's like, I95 for the water. And I'm just bombing in this boat. Not my boat. I don't own a boat. And I'm really, [crosstalk 00:01:12] I had this thing like pinned, you know, it was like 22 footer. It's like, it's really screaming. And then I'm like, Oh, this is a lot of fun. And then all of a sudden I see this big head pop out of the water and it's fricking thing had it been like 150 years old, this huge Brown tortoise.

Jason Rigby (01:26):

Oh that's so cool.

Alexander McCaig (01:27):

Oh my God! And like cut this thing left. People were almost flying out of the boat. I cut. Right. It was more important for me to save the a hundred plus year old tortoise than worry about all the people, the human lives that were in the boat at that moment. But he's just, you know, he's just in the middle [crosstalk 00:01:40] of the path. He didn't care.

Jason Rigby (01:42):

No.

Alexander McCaig (01:42):

He's just hanging out and you know, they have those little fins. [crosstalk 00:01:44]

Jason Rigby (01:46):

Just about everything eats turtles though. Right?

Alexander McCaig (01:48):

Wait, just about everything eats turtles. [crosstalk 00:01:49] Just about everything.

Jason Rigby (01:51):

Yeah. But I mean, I know like barracudas would eat EM, sharks eat EM.

Alexander McCaig (01:55):

Oh yeah. Well, listen, it's a lot of meat.

Jason Rigby (01:57):

Yeah.

Alexander McCaig (01:58):

You get through the shell.

Jason Rigby (01:59):

Yeah. Turtle soup. That used to be a thing.

Alexander McCaig (02:01):

You know what's nice though albeit turtle soup. I think it has.

Jason Rigby (02:04):

I've never had it. I don't think I could eat a turtle.

Alexander McCaig (02:07):

No. You know, turtles do a really good job of eating like jellyfish.

Jason Rigby (02:13):

Really.

Alexander McCaig (02:14):

Jelly Fish are way, way, way, way, way too overpopulated in the ocean. And they'll just go and they just swallow those things. Any of the nematocyst as the things that caused the stinging on your body.

Jason Rigby (02:23):

Yeah.

Alexander McCaig (02:24):

They're not completely unaffected.

Jason Rigby (02:25):

Oh. That's wild.

Alexander McCaig (02:26):

They just inhale these things. Just keep going. I just wish there were more turtles, cut back on these populations of these massive sea nettles that are 30 feet long.

Jason Rigby (02:36):

I know, but I mean, that one was in when Darwin was alive, just died I think.

Alexander McCaig (02:41):

What?

Jason Rigby (02:44):

It was alive, the one that he brought back from the Galapagos islands and it was in the London. It may either still be alive or it just died. One of the two [crosstalk 00:02:52] will have to go and look up. But you know, they live for hundreds of years.

Alexander McCaig (02:57):

Like I'm a Macaw.

Jason Rigby (02:58):

Yeah.

Alexander McCaig (02:58):

You know. Or a lobster.

Jason Rigby (03:00):

Yeah, a lobster can live literally, but there is a lot of creatures that can live forever.

Alexander McCaig (03:04):

Yeah if left undisturbed.

Jason Rigby (03:05):

So it's like, if I was Google and I had trillions, like they do, I would be having a whole, [crosstalk 00:00:03:11] all of these. I would say I want every single animal. [crosstalk 00:00:03:14] And then we're going to go through and inject me with all of this. I want to be a mutant.

Alexander McCaig (03:22):

Oh my God.

Jason Rigby (03:23):

I want to be Wolverine, something.

Alexander McCaig (03:25):

Professor Xavier [crosstalk 00:03:27] like rolls itself into the Google labs. [crosstalk 00:03:30] Jason woke up time to come to school. Jason.

Jason Rigby (03:34):

Now I see my money being used. Right.

Alexander McCaig (03:37):

Google, you did something right?

Jason Rigby (03:38):

Which we're going to talk about that with data scientist.

Alexander McCaig (03:41):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (03:42):

Here in a little bit. But for right now, we're going to get a little political.

Alexander McCaig (03:46):

Well, we're not going to get political. We're going to talk about people getting political.

Jason Rigby (03:49):

I thought we could get.

Alexander McCaig (03:53):

I'd rather not be divisive, right?

Jason Rigby (03:54):

No, yeah, no. We build bridges, create unity.

Alexander McCaig (03:57):

Yeah. So this articles on climate related deaths.

Jason Rigby (04:00):

Local weather related dying danger down 99.6% over a hundred years.

Alexander McCaig (04:06):

Okay.

Jason Rigby (04:06):

And then they said what's up with that? W A T T S, science joke.

Alexander McCaig (04:11):

Oh yeah. WATTS [crosstalk 00:04:15] classic check gives me a very intellectual charcoal.

Jason Rigby (04:21):

There's another one. We're going to do an archeological show with data.

Alexander McCaig (04:24):

I'm psyched on that one.

Jason Rigby (04:25):

There's one there. There's a funny one there too. Don't give up the trowel.

Alexander McCaig (04:29):

Yeah. I love that.

Jason Rigby (04:30):

Instead of towel.

Alexander McCaig (04:30):

Yeah. Yeah. Don't throw it in. Don't throw in the trowel. Okay, can we focus?

Jason Rigby (04:36):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (04:37):

So here's the thing. This dude, what's his name? Ori Olson. What's his, I don't know. Is he Norwegian or something?

Jason Rigby (04:44):

Double stuffed Oreo.

Alexander McCaig (04:45):

Yeah. Double stuffed Oreo. What's this guy's name and made this chart. Anyway, this guy puts together, this peer reviewed study and this peer reviewed study he posts, I don't know why you would do this. He posts the graph on Facebook. You know how many people look at graphs on Facebook and just lacks total context?

Jason Rigby (05:01):

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Alexander McCaig (05:02):

And they're like, Oh my God. I mean, climate change, it's not a thing, right? Like what, because deaths are going down. You have to tell me that just because of the number of deaths says that climate change is not legitimate. So just as the overarching theme of this article, a dude posts a chart on some sort of peer reviewed paper, showing that deaths are going down and then says that people that are, you know, trying to do something and advocating for policies to help combat climate change, it's all just some sort of belief system. That's what it is. So here's, what's interesting. He's like I'm posting data and I'm going to put other people and other scientists in buckets saying they're just a part of a belief system.

Jason Rigby (05:39):

Yeah. Which to me is interesting because when you look at, they were saying in 1920's, there was 485,000 average every year.

Alexander McCaig (05:47):

mm-hmm (affirmative).

Jason Rigby (05:48):

Deaths and then last year was 18,357.

Alexander McCaig (05:52):

Okay. But [crosstalk 00:05:53] you are percentage base graph. Right? So what do we have to consider?

Jason Rigby (05:56):

The population.

Alexander McCaig (05:57):

Population increase.

Jason Rigby (05:58):

Yes, yes.

Alexander McCaig (05:59):

We had a much smaller population, not too long ago, but for whatever period of time, you know, a hundred years ago, what was it? 550 million or something.

Jason Rigby (06:06):

You also had environmental impacts in the sense of, you had urban development. I mean, there was a lot of things going on. When you live in a concrete building, the winds, don't get you. The snow when you're living in a [crosstalk 00:06:18] tent outside and it's below 30.

Alexander McCaig (06:20):

It's different than being in a shanty. [crosstalk 00:06:22] You know what I mean? Or a thatched roof building.

Jason Rigby (06:25):

What is the average age of people living back in the 1920s, 30 or 40 years old

Alexander McCaig (06:30):

Yeah people are living longer. So every year that goes by as the longevity of life increases, plus the population increases, would naturally drive this ridiculous, you know, data skewed graph down to zero. And so this is, you know, this is a very important point that we want to focus on is that data can easily be manipulated.

Jason Rigby (06:49):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (06:50):

If someone does not give all of the pertinent information, the raw data that it was before, and then come to some sort of conclusion, that's not truly an observational conclusion. You can't just say, Oh, this graph has gone to zero, everything's false. It doesn't work like that. It's not correlated in that sort of fashion. We're also better at constructing things. We've built seawalls. We have incredible weather management, disaster recovery systems. There's all that stuff is going on. People are living longer in the populations increasing. Obviously that percentage-based number is going to naturally drive itself way down to zero.

Jason Rigby (07:25):

But, it doesn't. And I know TARTLES really concerned about this. It doesn't. And you know, we put our money where our mouth is with this. It doesn't negate. What is happening with the climate?

Alexander McCaig (07:34):

No, not listen. This does not negate it at all.

Jason Rigby (07:36):

Just because there's less deaths, whether this is even if this is true or false, it doesn't matter. Just because there's less deaths, doesn't mean what's going to be happening in the next twenty-five, fifty, a hundred years.

Alexander McCaig (07:48):

Yeah. And you, you know what that reminds me of, do you remember 2008, 2009 stock market crash?

Jason Rigby (07:53):

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Alexander McCaig (07:54):

People were like, no one will default on all this stuff. Not a chance. Everything was stable. Oh, the risk, it's just huge. [crosstalk 00:08:01] No, let's keep, let's keep, you know, taking these, you know, credit derivatives and we'll keep repackaging them. And then just say that the risk is just, it continues to drop down.

Jason Rigby (08:10):

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Alexander McCaig (08:10):

Because we put them in buckets. And then what happened? One little event, which you assumed wasn't going to happen, in some perceived state of stability, rocked everything.

Jason Rigby (08:20):

You get the, I forgot what they call it. Oh, I wish I knew it was some type of effect, you know? But once something gets instable.

Alexander McCaig (08:28):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (08:29):

They even wrote a book on it, a guy wrote a book on it's amazing book. It's called "The Antifragil"

Alexander McCaig (08:33):

Yeah. His name's Nassim Tara.

Jason Rigby (08:35):

Yeah.

Alexander McCaig (08:35):

Or something like that.

Jason Rigby (08:37):

Yeah. I think you're exactly right.

Alexander McCaig (08:38):

He was talking about the Black Swan affect.

Jason Rigby (08:40):

Yes.

Alexander McCaig (08:40):

And so things will become, you know, you want to make things anti fragile with how you balance your stock portfolios. But the idea is that you got to look out for these black swans, these events that you never think are going to happen. And you're skewing all this data to yourself, that is giving you some sort of false, you know, perspective on reality that you operate one way. And then you just get slammed by something that was unseen. You thought was never possible until it was possible.

Jason Rigby (09:04):

Yeah. Because deaths are down, but yet we may not have Florida in what? 50 years?

Alexander McCaig (09:09):

Yeah. Florida might not me there in 50 years. And because the death rate is down so much, well what happens when you have just this massive disaster.

Jason Rigby (09:17):

Right.

Alexander McCaig (09:17):

Oh my God. That the chart just hockey sticked.

Jason Rigby (09:20):

Has it, have they ever seen, I mean, and this is legit data that they have out there, with one degree temperature raise.

Alexander McCaig (09:28):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (09:28):

The oceans and stuff like that. What happens? It's crazy. Like California is gone. Florida's gone.

Alexander McCaig (09:33):

No it's terrible, because if it increases a little bit and you can just use Greenland for an example, the thermal temperatures right in the sun, it has an interesting interaction. So the ice begins to melt and as it gets down deeper, the color goes from that beautiful white, light blue.

Jason Rigby (09:52):

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Alexander McCaig (09:52):

Which has an albedo effect. And which is it, it reflects so much sunlight in its natural state. But when we start to bring that down, you get the darker colors stuff that likes to absorb heat. So then it begins to melt faster. And then you got this fresh water melt just pouring into the ocean. So that causes that stuff to rise. And it also that freshwater starts to go through a desalination process. And so that means the earth can freeze a lot quicker. And then you're just like, wow, things are getting really hot, only so it can drive you into another ice age. How many people are going to die in an ice age? Every single one of us.

Jason Rigby (10:24):

Every single one. Yeah.

Alexander McCaig (10:25):

We're not going to last for a 10 million year ice age I can tell you that.

Jason Rigby (10:29):

No, exactly. And, it's our planet and it's our responsibility, regardless if you're conservative, liberal, doesn't matter.

Alexander McCaig (10:35):

Yeah.

Jason Rigby (10:36):

It's your responsibility. And each of us has a responsibility to take care of our planet.

Alexander McCaig (10:40):

That's precisely correct. And when you say, put out a graph like this with, and you skew data,

Jason Rigby (10:44):

mm-hmm (affirmative).

Alexander McCaig (10:44):

And you put it out without any sort of context for people, it almost like issues the responsibility. You only have to worry about it, look at this graph. Not a big deal. That's not even all the data. That's just like someone coming up with some sort of thing saying you know, we peer reviewed it. And what you think is just a belief system. Well, that's just not true. Look at all the data. These are the things you have to be careful well, you be careful of. What's nice about, TARTLE is that everybody can purchase that data.

Jason Rigby (11:11):

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Alexander McCaig (11:12):

Not just one scientist gets to analyze it. All of them get to analyze it. So it's not like one person say, Oh, I have my own special data set that nobody else has. I'm going to publish a paper to look good real quick. It's like, everybody can have a big, like bullshit filter on each other.

Jason Rigby (11:25):

No, I love that.

Alexander McCaig (11:25):

No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. Yes. That's correct data. That's that's not, that's, it's totally nonpolitical. It's, non-dogmatic, very agnostic. You know? It's very forward-looking. I like that.

Jason Rigby (11:35):

And we'll get into that a little bit more when we get into the data scientists episode about how they are looking at data.

Alexander McCaig (11:42):

Yeah. And this, you know, listen, it's, it's just as much as a scientific thing as it is an ethical thing.

Jason Rigby (11:46):

Yeah. And it's regardless of what country you live in, understand it's humanity's responsibility.

Alexander McCaig (11:53):

Yep.

Jason Rigby (11:53):

With all This great technology comes great responsibility.

Alexander McCaig (11:56):

Yeah. It's the big double-edged sword.

Jason Rigby (11:58):

Yes (affirmative).

Alexander McCaig (11:59):

You know, you can do a lot of good with it or you can do a lot of bad. So why don't we make the right choice?

Jason Rigby (12:04):

Yeah. And shout out to Pakistan.

Alexander McCaig (12:06):

Yeah (affirmative).

Jason Rigby (12:07):

For signing up like crazy on tartle.co.

Alexander McCaig (12:09):

Pakistan, I don't know what you guys are doing, but you're all.

Jason Rigby (12:13):

Shout out to us. We'd love to be able to [crosstalk 00:12:15] you're all fired up about it. Yeah. That's awesome.

Alexander McCaig (12:16):

Yeah. Thanks guys.

Speaker 1 (12:25):

Thank you for listening to TARTLEcast with your hosts, Alexander McCaig and Jason Rigby. Where humanity steps into the future and source data defines the path.